Profits for Spotify, Pennies for Artists

by Josh Rosenberg

--

By any reasonable standard, New York singer-songwriter Blake Morgan has had a good ride as a professional music artist. At age 28 in 1997, he worked with Led Zeppelin’s record producer Terry Manning to create his plaintive, screeching-electric-guitar-drenched alternative-rock debut album, Anger’s Candy, for which Washington Post critic Mike Joyce hailed him as “a natural when it comes to fashioning sharp melodies and catchy choruses.” Lenny Kravitz contributed to one of the Candy tracks, and he toured with Joan Jett as an opening act. Billboard magazine declared that Morgan possessed “a voice that was made to be heard on the radio” — a voice with a passionate, raspy, anthemic sound that would make inspirations like Bono and Dave Grohl proud.

When Morgan first made these big splashes in the pre-millennium era of the late ’90s, it was the height of the heyday of CD sales. In 1999, The music industry was grossing an all-time annual high of $22 billion in sales, according to the Recording Industry Association of America. Morgan had every reason to believe he’d arrived as an artist. “I was a very hot commodity all of a sudden, getting a lot of attention,” Morgan recalls, “and I came out the gate with something great.”

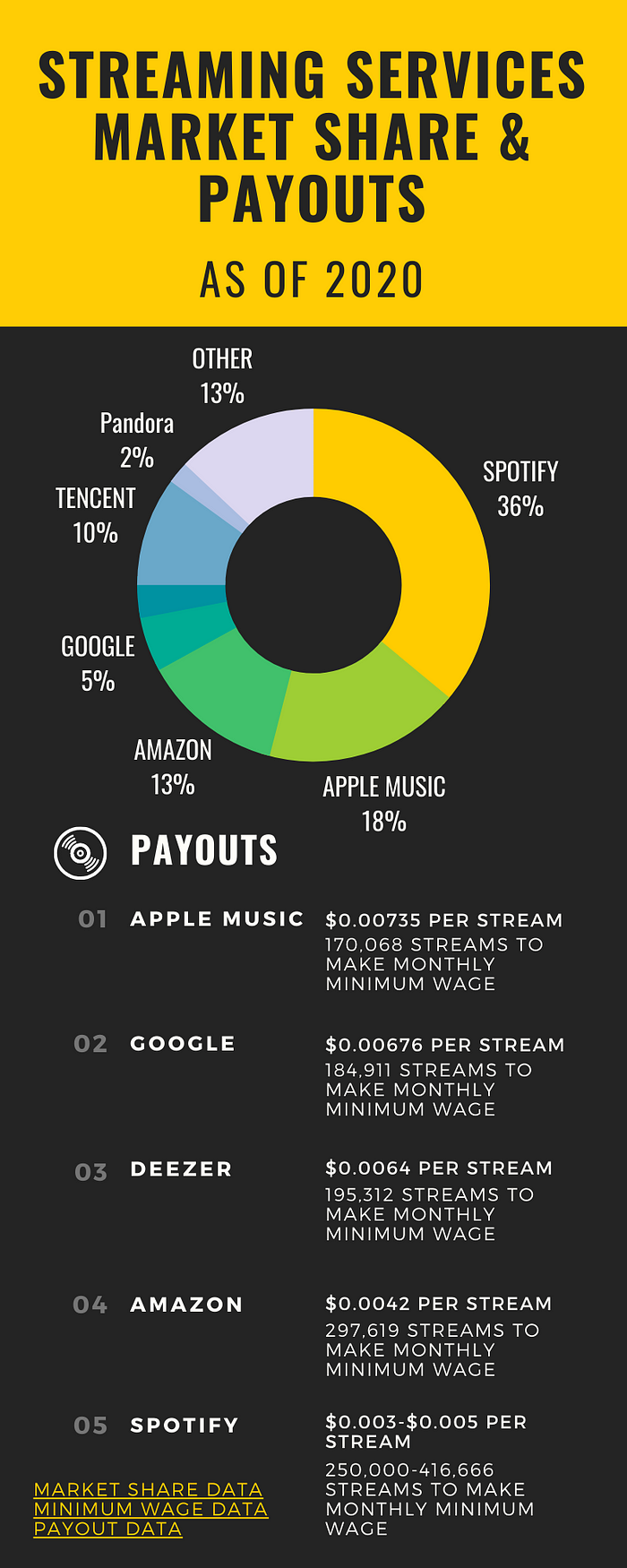

Despite his auspicious launch and three subsequent well-received albums in 2005, 2006 and 2013, Morgan, now 52, has essentially become a footnote as a performer. He’s one of over three million artists in a streaming-music market where the leading subscription service, Spotify, hogs one-third of all market share and offers listeners instant access to virtually every track ever recorded. In such an environment, the leading credo is to go big or go comparatively unheard. Morgan’s music has generated only around 30,000 streams to date on Spotify for his most popular songs, while global favorites like Drake and Cardi B have racked up half a billion streams on their most recent hits alone.

Let’s break that down for a moment in financial terms by comparing then to now. 30,000 sales of a single song from a 12-track album would have netted the artist nearly $2,118 back in the late 1990s, according to Greg Kot, co-host of the Chicago Public Radio show Sound Opinions and author of the book Ripped: How the Wired Generation Revolutionized Music. Thanks to the strength and comparatively high price of physical-media sales, CDs of full-length albums typically went for $16.75 apiece at that time. On Spotify however, artists currently make roughly about $0.003-$0.005 (one-third of a penny to one-half of a penny) per song stream. So, 30,000 streams only come out to about $150 — not even enough for two weeks of groceries.

You may think all this makes Morgan just another random obscure music artist. (New York and Los Angeles, among other magnet cities, certainly have lots of them.) But his story is in fact an important marker for a whole class of musicians who simply can’t survive on earnings from their music alone, even as the corporations who control their destinies make hundreds of millions.

Refusing to go down without a fight, Morgan has spent his career trying to make people more aware of the many ways the music industry can wind up crushing the majority of artists who keep it going. In 2002, he founded Engine Company Records Music Group, an independent recording label. Among the host of musicians he has attracted, notable entries include Tracy Bonham, a Grammy-nominated violinist, and James McCartney, son of legendary Beatle Paul McCartney. Many of these artists work in tandem with one another as backing instrumentalists and vocalists on each other’s albums. Morgan continues to release his own music as well. Since the label is his own, he gets a larger share of streaming service payments, but for those with different publishing and recording contracts, or multiple band members, artists usually make significantly slimmer royalties.

“I never wanted to work on the Death Star,” Morgan says. “I wanted to work on the Millennium Falcon. It’s faster, you can pivot quicker, you can zoom in and out of the asteroids, so you don’t get hit, and your defeats are softened because you’re going through them together. But also, the Millennium Falcon wins.”

It’s a very romantic analogy. However, the true challenge facing artists like Morgan is that the systems that have been created to sell music as easily as possible to a vast global audience at the lowest possible subscription prices only truly works for the top 10 percent of artists. The other 90 percent are stifled by insufficient pay and milked for all they’re worth by one-sided contracts.

Major recording labels have always been king-making investment houses. They market the music and manage the careers of artists who have to fight tooth and nail to escape being mistreated financially. But digital distribution services have now come along and upped the parasitic ante. By dominating global market share and distributing millions of songs for the labels, companies like Spotify are piggybacking on the music industry’s already exploitative system and magnifying it exponentially. The more content you control, the larger the overall profit–even if the overwhelming majority of content creators are essentially starving.

“Music has [become something] run by bean-counting tech people who don’t understand anything about music,” says Morgan. “They’re all just widget people.”

Spotify’s total revenue in 2019 was their highest to date at approximately $8.28 billion. And yet, in roughly that same period, a study conducted by Broadbandservices, a UK-based company that rates and compares internet service providers, found that an artist would have to have over 3.5 million streams annually just to make the federal minimum wage of $7.25/hour. It doesn’t take rocket scientists to figure out that with that kind of income stream, Spotify could probably afford to pay artists more.

potify’s total revenue in 2019 was their highest to date at approximately $8.28 billion. And yet, in roughly that same period, a study conducted by Broadbandservices, a UK-based company that rates and compares internet service providers, found that an artist would have to have over 3.5 million streams annually just to make the federal minimum wage of $7.25/hour. It doesn’t take rocket scientists to figure out that with that kind of income stream, Spotify could probably afford to pay artists more.

Spotify, however, doesn’t see it that way. In fact, CEO Daniel Ek recently provoked the ire of artists when he stated that the onus is on musicians, not Spotify, if they aren’t happy with their earnings.

“Some artists that used to do well in the past may not do well in this future landscape,” Ek told MusicAlly’s Stuart Dredge, who has been covering Spotify, and the music business at large, for over a decade. “You can’t record music once every three to four years and think that’s going to be enough.”

A large number of musicians hit back on social media, outraged and appalled at Ek’s suggestion to work even harder for less. Dee Snider, the lead singer of Twisted Sister and composer of the classic song “We’re Not Gonna Take It,” tweeted, “The amount of artists ‘rich enough’ to withstand this loss are about .0001%. Daniel Ek’s solution is for us to write & record more on our dime?! Fuck him!”

R.E.M.’s Mike Mills had a similarly salty reaction. “’Music=product, and must be churned out regularly,’ says billionaire Daniel Ek,” Mills commented. “Go fuck yourself.” However, when a fan suggested boycotting the streaming service, Mills replied, “Boycotting Spotify won’t help the musicians on there.”

Ek and Spotify have yet to respond to the widespread backlash, but it’s clear from his comments that payout rates aren’t going to increase anytime soon.

In a valiant attempt to combat this oligarchic situation, a battery of non-profit organizations has tried to make a stand by lobbying Congress and advocating for fairer compensation for artists. One such group is the Future of Music Coalition in Washington D.C., and its leading officer, director Kevin Erickson. Before taking the reins at Future of Music Coalition, Erickson specialized in community organizing and policy. He led Positive Force DC, an activist network of music venues and youth concerts aimed at promoting radical social change in the industry. But after a decade of fighting, he and others like him still seem to have their work cut out for them.

According to Erickson, one big issue is the way the industry makes organizing more difficult than it might be for, say, standard, full-time, office-based workers (and certainly COVID’s impact isn’t helping). “There are some situations where [artists] have collective bargaining tools,” he explains, “such as the performance rights organizations that represent songwriters. But in the broader marketplace, everything is so individualized that everyone is forced to advocate for the best deals for themselves.”

Most touring musicians have to sign contracts with different clubs and venues around the country every night throughout their tours. Each one has its own terms and conditions. But in the digital marketplace, there are even more limited avenues for negotiation.

“In more traditional employment relationships, you have one employer,” Erickson says. “For musicians you have, more typically, a bunch of different income streams that hopefully add up to a living.” Because of this structure, musicians usually lack the kind of workplace protections and benefits that traditional employment offers.

As Erickson sees it, streaming executives believe that they treat artists better than free alternatives such as YouTube or piracy, because at least they’re paying something. But that assessment isn’t entirely true. Saying that your service is “better than piracy,” only reinforces the idea that companies like YouTube and Spotify are the last bastions even willing to pay artists for what is essentially free to acquire online illegally.

“We’re going to need real investment in the arts, in a large and long-term way,” says Erickson. “We need to make sure that support is not just going to institutions but also to artists, and that real infrastructure is built that can reinforce and support sustainable careers.”

Currently, there are two major unions that represent musical artists: for instrumentalists, there’s the American Federation of Musicians, and for vocalists, there’s the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (a.k.a. SAG-AFTRA). Each of these potentially helpful organizations have eligibility obstacles. For more traditional employment, such as salaried orchestra members or film score musicians, they’ve been successful. But for touring musicians and independent producers, most contracts are one-to-one transactions. They involve an overwhelming variety of different publishers and revenue streams, which makes improving conditions and organizing much more challenging.

Gaps in legal representation, marketing and healthcare are where major label leverage can step in. But according to Erickson, this is where much of the exploitation occurs between labels and artists–and it happens even before Spotify steps in.

Streaming platforms like Spotify do not pay artists directly. They pay for bulk agreements with major labels, publishers and copyright owners. That means a lot of other hands in the pot before any money lands in the hands of any one artist — and a pie with so many slices that no one slice provides sustenance. Spotify’s payout per artist thus becomes desperately meager–and according to The New York Times, it’s not even the last stop in a chain of financial insults. Most major labels then take between a roughly 50 to 85 percent cut of the overall Spotify payout.

Profit splitting can be avoided by going independent and making a direct licensing deal with Spotify, as Blake Morgan’s ECR Music Group does. But the number is usually determined by how much money the artist is expected to generate for the label. As with so many aspects of the music business, a catch-22 rules here. You can go independent to make more of a profit per recording but being part of a label gives you more leverage when making deals, since you now have the backing of being part of a larger catalog of musicians.

Andrew Nietes, an associate attorney at Latham & Watkins in New York City and a former emerging talent associate for Atlantic Records, says, “There are different contracts for fresh faces than there are for more established artists.” He warns that “artists can get exploited if they don’t read the fine print.”

Case in point: the seven-album deal. While five album deals over the course of six to eight years are quite standard in the industry, younger artists without good legal representation are often enticed to committing to seven albums, locking them into disadvantageous 15/85 percent cuts on royalties regardless of their success.

“You don’t want to get into a situation where you’re signing something and then you’re obligated to this company for the next 10–15 years,” said Cassandra Spangler, 38, an entertainment and music law attorney in New York. “Especially if you’re a very young artist. That’s going to be most of your career.”

Spangler, who has spent the last decade representing young producers, says her clients have begun making more demands as payout rates remain inadequate. She specializes in helping beat makers in hip-hop register copyright for their work, but some asks, like outright ownership of recording masters for the artist in question, are difficult intellectual property rights to win even if you’re a global superstar. (Example: Taylor Swift, a multi-platinum selling artist with over 47 million monthly listeners on Spotify, recently had her master recordings sold by her former manager to a third party. She will have to re-record her entire early discography if she wants to see more revenue from those albums. Reportedly, she plans to do just that.)

“Unfortunately, in most situations, unless you’re a very established artist with a lot of leverage, it’s very difficult,” Spangler says. “When you sign with a label, the label is making an investment in them. They’re going to want things, like owning the masters, to get a return on their investment.

From a business perspective, there are some fair aspects to such a relationship, with the label acting as a bank giving out loans to aspiring artists. But the artist has to have as much trust in the label’s abilities as the label does in the artist for it to work.

Blake Morgan, the singer-songwriter anointed by Billboard as “made to be heard on the radio,” initially put a lot of trust into the first record label he worked with. Disappointingly, as Morgan relates, “It was a total disaster.”

In 1996, Morgan signed a contract with Sony Music’s Phil Ramone (no relation to The Ramones). He seemed like a great potential career partner: a well-known record producer with clients such as John Coltrane and Billy Joel. Ramone had his own imprint at Sony named N2K. It was a company known for early innovations in how to link recording musicians in different locations in real time. But despite that, the N2K label had difficulties promoting Morgan’s record and getting it on the radio. Morgan chocked up the failure to a lack of adequate support staffing at N2K, a lack of leverage on Ramone’s part, and some very reckless decision making.

“With big labels, you need to be able to leverage things when you go into a radio station,” Morgan says. “N2K had no leverage with [any] radio guy, where every other label had [like] 40.”

The week of March 15, 1997, when Morgan’s debut record was released, the label took out a back-page advertisement in Billboard magazine. Morgan believes it must have cost them nearly $100,000. (Based on Vogue’s $157,000 cost for a full-page ad in 2015, or The New York Times’ similar $107,000 price in 2019, his figure seems like a reasonable estimate.)

Morgan recalls that the ad angered a lot of other labels who were fighting for that space, such as Columbia’s release of Aerosmith’s twelfth studio album, Nine Lives. He felt that such a large outlay should have gone toward touring costs instead of for a one-shot piece of promotion.

Morgan’s next step was to ask to be released from his contract, which, since N2K was still a burgeoning label, meant dealing with Ramone himself. Initially, the label balked. They offered instead to sell Morgan his own domain name, “Blakemorgan.com,” which they owned, for $100,000. Morgan remembers thinking, “You just want to make back all the money you wasted on that ad by selling me my own name.”

The label eventually folded when it went bankrupt in 1998. It was subsumed by CDNow, a billion-dollar online shopping site subsequently taken over by Amazon. Through this legal implosion, Morgan found himself able to wriggle out of his contract. It wasn’t so much a victory as a forfeited game. As he saw it, he was now free of being exploited and dictated to by a major label.

In 2002, Morgan started ECR Music Group so that, “all that energy could go into the music part of it instead of constantly trying to get deals.” But it turned out starting his own label had not prepared him for facing off against streaming services. In 2019, music streaming providers such as Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, Tidal, and Pandora, made up 80% of the industry’s market share, with Spotify leading the pack at 36%.

For artists up against these tech giants, it seems incredibly daunting to fight the powers that be. It can’t be ignored how amazing $9.99/month for unlimited streaming is for listeners. It’s also naïve to suggest that things will change just because things aren’t fair for artists. These are two constants that Spotify and the major labels are well aware of. Record executives and listeners alike would have to make major concessions, and face higher costs, to truly value and pay musicians more.

“The battle between art and commerce has always been awkward, but to try and be an artist now is harder than it has ever been in human history,” says Morgan of himself and fellow music artists. “We all get screwed over, but in music, why does it need to be this way?”

You can listen to and support Blake Morgan’s music here.